In the Colorado Rockies

Where the snow is deep and cold

And a man afoot can starve to death

Unless he’s brave and bold

Oh Alfred Packer

You’ll surely go to hell

While all the others starved to death

You dined a bit too well

— from The Ballad of Alfred Packer

When accounts of rich gold strikes in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado began to circulate throughout the country in 1874, another small gold rush began. Alfred Packer joined a group of men from Utah heading to Colorado to try their luck at prospecting.. Twenty-one men set out in his group. They had high hopes but low provisions. Worst of all, they started out during snowy weather. They ignored the advice from Chief Ouray–whom they met along the way–to wait a few more weeks. Impatient, and angry with each other, they split into three small groups to journey onward. After considerable hardship, the members of the first group arrived at the Indian Agency. Weeks later Alfred Packer, who was in the second small group to leave Chief Ouray’s camp, arrived at the agency alone. None of the others in this group had made it. Parker gave many differing accounts of what had happened during the journey. What each of these accounts had in common was a confession of theft, murder, and cannibalism. Whichever version of the fate of the small group of men was true, and however and suffering those men faced, one fact remained: Alfred Packer was a liar and a jerk.

In April 1874 a lone prospector, Alferd Packer, came walking into the Los Pino Indian Agency in Colorado. He had a Winchester rifle over his shoulder, his feet were wrapped in strips of blanket, and his hair was matted. The employees of the Indian Agency who saw him approaching rushed to bring him inside. When he was asked about the five other men who had been with him, Packer stated that he didn’t know where they were. He explained that the original large group had broken into three smaller groups. In fact members of the first group that had left ahead of Packer had arrived many days earlier at the agency. Packer explained that while traveling with his small group, he injured his leg, fell behind, and became separated from the others. In fact, he expressed surprise that the others hadn’t arrived well ahead of him. Packer insisted he didn’t know where they might be.

Days passed and the other members of his party never appeared. Men from the first group of the original Utah party noticed that Packer now had money. They knew that when he started the trip in Utah, he was poor. Where had the money come from? Suspicions were aroused. It was suggested that Packer lead a search party up the trail he had come to find the missing men. He did so, but the search was unsuccessful when Packer became confused and said he couldn’t locate the exact route he had traveled.

Then came disturbing reports that up the trail from which Packer had so recently emerged, mutilated bodies had been found in the snow at what seemed to have been a prospector’s’ camp. During the questioning, Packer kept changing his original story of what happened on the journey. An investigation began. Could Packer be both a murder and a cannibal?

Alfred or Alferd?

His birth certificate give his name as Alfred Packer, but he sported a tattoo that spelled his name Aferd Packer. (Or the tattoo artist made the error, which amused him, and he subsequently adopted it — depending on which account is to be believed.) He was known to spell it this way on other occasions as well. Packer was born on November 21, (some say January 21), 1842 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Before leaving home and striking out on his own, Packer apprenticed in a small printing establishment. Holding a job and searching for employment was made difficult because he sometimes suffered from epileptic seizures. These seizures were at times severe. His desire to cover up this affliction was no doubt one of the reasons why Packer lied to glibly and so frequently.

On April 22, 1862, during the Civil War, twenty-year-old Packer joined the Sixteenth Infantry in Winona, Minnesota. He was honorably discharged from the Union army on December 29, 1862, as “incapable of performing duties of a soldier because of Epilepsy.” Packer didn’t give up serving in the army easily. He tried to cover up his disability and joined the Iowa cavalry. Again, he was discharged. After that, Packer held a number of different jobs including teamster, miner, hunter, trapper, and guide. While working in Georgetown, Colorado, as a miner, he lost portions of the index and little fingers of his left hand. These physical deformities combined with a high, raspy voice made him easy to identify and remember.

A Fateful Journey

Packer left Colorado and moved to Utah where he lived in the town of Sandy, Twelve miles south of Salt Lake City. He worked in a smelter and did a little mining without much success. News reached him of rich ores being discovered in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. Learning of a small group of men being organized to go to Colorado, Parker had very little money, but he agreed to pay twenty-five dollars and work out the rest by tending two four-horse teams on the journey. He said that he’d driven ore wagons in some mining camps, which gave him the expertise to guide, but it turned out to everyone’s misfortune that he actually knew very little about the area to which they were going.

The group of men who headed for Colorado ranged in age from the eldest, Israel Swan, who was almost sixty, to the youngest, George Noon, who was only nineteen. Among the party were several prospectors, a butcher, a physician from Scotland, a Frenchman named Jean “Frenchy” Cabazon, two Irishmen, and a young man known as Italian Tom.

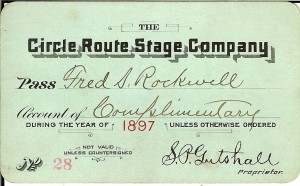

In late autumn 1873, the party of men left Bingham and picked up Preston Nutter and his wagon and team in Provo, Utah. He claimed to have been the guide for this expedition, but there is evidence that this may have been an exaggeration if not an outright fabrication. In Salina they picked up the last member of their group, a man who had journeyed there by stagecoach. Now numbering twenty-one men, they started on their 325-mile journey to the Colorado border. They followed the Mormon Trail that had been used earlier by Brigham Young and also the Pony Express. Apparently some of the food supply was lost along the way, and the would-be miners grew hungry and desperate. They survived for a time on chopped barley, which had been brought along as food for the horses.

The crossing of the Green River, eighty-five miles from the Colorado border, was especially difficult. They ended up making a raft. They disassembled the wagons, ferried them over, and re-assembled them on the other side of the river. This proved very time consuming. They started traveling again only to find themselves surrounded by Native Americans who took the to the camp of Chief Ouray about two miles south of the present-day Delta. Ouray welcomed them, and the weary men rested for awhile in camp. At that time of year, the mountain passes were treacherous, the Ute said, and snow could bury men. It would not be wise to proceed.

Nevertheless, a handful of these prospectors could not wait. They wanted to get to the mines before anyone else. Five of them, frenzied by the prospecting spirit, decided to risk all and continue over the mountains to the Los Piños Indian Agency on Cochetopa Creek near Saguache and Gunnison. Packer joined them.

Chief Ouray told these men to follow the Gunnison River to “cow camp,” a government cattle camp, “seven suns” away.With a ten day supply of food for a 75-mile trip (they apparently thought it was 40), the doomed men who left Chief Ouray’s camp with Packer were Shannon Wilson Bell, Israel Swan, James Humphrey, Frank ‘Reddy’ Miller, and George ‘California’ Noon, who was only 18. Aside from Packer, that was the last time anyone saw these men alive.

Before they left Ouray’s camp, however, there was a dispute among the eleven men and they broke into two groups. Five men left on February 6, became lost, and nearly starved. But after three weeks, they managed to reach the government cattle camp. They rested and went on again in spite of further terrible travel conditions. They were half-dead when they finally succeeded in reaching the Los Pinos Indian Agency.

Alferd Packer and his group of six left Ouray’s camp on February 9, 1874. They had provisions for about ten days. Two of the men had rifles, one a skinning knife, and one a hatchet. Packer was unarmed. Thinking that the trip would take about a week, they hiked off in a southeasterly direction and almost immediately found themselves in the midst of a snowstorm. It was sixty-five days later, on April 16, when Packer, all alone, arrived at the cow camp and was taken in. Packer told the story that he had been left behind due to fatigue, frozen feet, and snow blindness, and said he had continued on his own.

Oddly, when he arrived, he had several wallets in his possession from which he extracted rolls of money, and although he professed having gone for more than a day without food, he asked for nothing to eat. He just wanted some whiskey. He mentioned that he’d hurt his leg and had fallen behind, so he was not sure where the others from his party were. He had expected them to beat him out of the mountains.

Packer repeated this story not only to strangers but also to those at the agency who had been in the original large party from Utah. Preston Nutter was one of the original party who had seen the other two small groups leave but had decided to remain in Chief Ouray’s camp until the weather improved. He had only recently arrived at the Los Pinos Agency after an uneventful two week journey.

Packer eventually went on to Saguache with two of the men from the original prospecting party. He spent quite a bit of time in the Saguache saloon, repeating his story. Still the other five men from his small group never appeared. The missing men and the fact that Packer suddenly seemed to have quite a bit of money made his earlier companions suspicious. One member of this old traveling party noticed that Packer now carried a knife that had belonged to one of the the other prospectors in Packer’s party.

People who listened to his tales at the saloon thought that he’d taken the dead men’s possessions. Then, an Indian guide walking along the trail found strips of meat, which turned out to be human flesh. Packer’s tales began to sound like outright lies. From all appearances, he had killed the others, survived off their meat, and enriched himself with their assets.

When Packer bought a horse, a saddle, and clothes, he paid one hundred dollars in cash, and the seller observed that Packer took some of the money from each of two billfolds. The Indian agent, Charles Adams, and his wife stopped in Saguache on their way back to Los Pinos Reservation from Denver. When Adams heard all the stories about the missing prospectors and all the money Packer was spending, he also grew suspicious.

The pressure was on to get a coherent account out of him.

Packer’s Confession

General Charles Adams

General Charles Adams

Adams suggested that Packer come back with him to the agency to lead a search party for the missing men, which Packer agreed to do. Adams asked Packer where he got the funds he was spending, and Packer told him the money was a loan from the village blacksmith. When Adams checked on Packer’s claim, he learned it was a lie. No loan had been made. Thoroughly alarmed now, Agent Adams began a long interrogation of Packer.

Packer eventually gave a confession that was quite different from the story he had on arrival. He said the winter weather had quickly overtaken the little party of prospectors, and they were near death from cold and starvation. Sixty-five-year-old Israel Swan died about ten days into the trip. Packer stated he was eaten by the five survivors. Four or five days later, James Humphrey was eaten. The Frank Miller died from an accident and he, too, was eaten. With only three men left alive, Packer said that Shannon Bell killed nineteen-year old George Noon, and then came after Packer with a hatchet. Packer said he shot Bell in self-defense.

“Bell wanted to kill me,” Packer’s report indicates, “struck at me with his rifle, struck a tree and broke his gun.” So Packer had killed him first.

And that left only one.

Why Packer had not offered this tale immediately upon returning to the settlement is not made clear in his confession, and perhaps was not even questioned. He swore that this statement was the truth “and nothing but the truth, so help me God.”

Adams wrote down this version of the events, woke up the justice of the peace, had Packer sign his confession in the presence of the justice of the peace. The Indian agent also sent a report of this version of Packer’s confession in a letter to his superior, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C..

The search parties for the bodies, which Agent Adams organized, failed when Packer said he was lost at the point in the trail where the searchers approached the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River. The members of the search party were suspicious enough of Packer that they wondered if he might have killed the others in his group and dumped their bodies in the lake. The searchers actually broke up a beaver dam to lower the water level and carry out a water search. They found no bodies.

After the search party returned to the agency, Packer was arrested on suspicion of homicide even though no bodies had been found. Since there were no jails available at the agency, Packer was sent to Saguache where a small stone structure on Sheriff Amos Wall’s ranch was used for a jail.

A Grisly Find

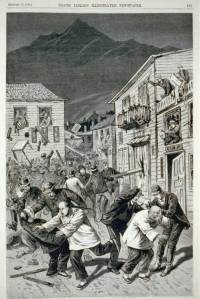

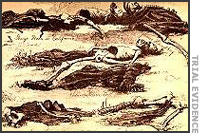

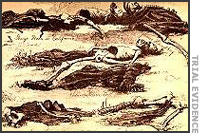

Of course the case drew attention and filled the local papers. In August 1874, John A. Randolph, an artist sent out to Colorado for Harper’s Weekly Magazine. A huge story broke out when the bodies of the missing men were finally found. Another report, printed in the Rocky Mountain News on August 28, 1874, said that Captain C.H. Graham of Del Norte found the bodies.

Whoever found the bodies were relatively well-preserved in the snow, and they showed clear signs of mutilation. One was missing its head, which it was surmised might have been carried off by wild animals. The other heads showed signs that had suffered blows, and all personal property was missing form the area except for a few blankets and tin cups.It did not look as if the men had been camped longat the site, perhaps only for one night. There was no evidence of a struggle at the campsite.Randolph spent some time at the site, sketching them all in a detailed composition that would be immortalized, and then reported his discovery. The area of the grisly find was promptly named “Dead Man’s Gulch.”

Sketch of remains as found

Sketch of remains as found

The Hinsdale County coroner, W. F. Ryan, along with a coroner’s jury was impaneled and an inquest was held at the scene of the murders, but unfortunately for history, he put nothing into writing. The remains were identified by one of the original twenty-one men who had set out from Utah. The bodies were buried on a high bluff nearby, and each grave was marked with a wooden post showing the name of the occupant.

Immediately a warrant was sworn out charging Alferd Packer with five counts of murder. The warrant was issued on August 22, 1874 in San Juan City, Hinsdale County. The handwritten warrant read, “Now therefore it is your duty to use all due diligence in arresting and bringing to Justice that said Al. Packer, and if taken, you are commanded to bring him before me…” Squeezed in after the phrase, “and if taken,” was added “dead or alive.” Before the warrant could be served, however, another piece of news broke, Alfred Packer had escaped from the irons of his makeshift jail on Sheriff Wall’s ranch near Saguache.

The day of the escape, Sheriff Amos Wall was in district court at Del Norte. There were rumors that he may have been in collusion with Packer on the escape, but nothing was ever proved. Little more was mentioned about the murders or about Alfred Pacer until a year later when a human skull was found about a mile from the murder site. There was speculation that this was the skull of Miller whose headless body had been found with the other murdered prospectors, and that animals had carried it off from the campsite. Interest peaked, and then faded.

Caught

Years passed before the name of Packer claimed headlines again, this time as the result of a chance meeting at Fort Fetterman. The fort was to be used as a supply base in 1867 at the junction of La Prele and the North Platte River. It was located about 135 miles north of Cheyenne, Wyoming. Eventually the government gave up the fort and it was used by civilians. In one of the buildings travelers could obtain board and lodging. A frequent traveler who know the fort well was “Frenchy” Cabazon, who had been with the original part of twenty-one prospectors who left Utah with Alferd Packer. Cabazon was now an itinerant peddler who sold household goods from his wagon.

In March 1883 Cabazon was in Fort Fetterman when he was approached by a man whose voice seemed somewhat familiar. The man gave his name as John Schwartze. Noting the missing fingers on the man’s hand, Cabazon felt certain it was Alferd Packer. Cabazon, however, did not indicate that he recognized Packer and promised to pick up some mining tools that were requested and bring them back in this wagon on his next trip. Cabazon then reported to the deputy sheriff in the vicinity that he had found Alferd Packer.

A flurry of activity followed before Alferd Packer was arrested by Sheriff Malcolm Campbell of Converse County on March 14, 1883, about thirty miles from Fort Fetterman in Wagonhound where Packer had been living. Packer admitted that he had escaped from jail and be been passed a key to unlock the irons he was in, but he never identified who had helped him.

Packer was delivered to the sheriff of Hinsdale County in Cheyenne, placed in manacles, and escorted to Denver by train. When he arrived at Union Depot on March 16, about a thousand people turned out to catch a glimpse of him. By this time, the newspapers were calling him the “ghoul of the San Juans.”

Back in the hands of authorities, Packer made a confession. This second confession was quite different from both his original story and the first written confession he had made out. Now Packer claimed that his little expedition had run out of food on the fourth day but managed to survive for several more days on what little they could find, which was mostly rose hips and pine gum. Pacer said that he went out to search for food, and when we returned to camp he found Shannon Bell eating Frank Miller’s leg. The three others in the party had all been killed by a hatchet and were laid out next to the campfire.

When Bell then attempted to kill Packer with a hatchet, Packer said he shot Bell with his hunting rifle. When Bell fell forward and dropped the hatchet, Packer too up the hatchet and struck Bell in the head. This took place on about the eleventh day of the expedition. Since the snow was so deep that he could not travel, Packer said he remained there near the camp for sixty days, awaiting spring and surviving by eating his dead companions.

Finally, when the snow looked to be thawing and crusting over, Packer packed a few pieces of human flesh, a gun, $70 dollars he had found on the men, and went on his way. Just before he reached the Agency, at his very last camp, he consumed the last pieces of meat. (He does not account for how some strips of human flesh were found along the way.)

He admitted that when he had led the 1874 party in search of the bodies, he had not gone all the way back because he had not wanted to venture closer to that site.

Packer added that he had escaped from jail by using a penknife as a key and had initially gone to Arkansas and Arizona before heading to Wyoming.

Once again, he claimed that this was a true confession, voluntarily made and sworn before a notary public. It was not his final version of the story.

Tried for Murder

After making this second confession, Packer was escorted from Denver to Gunnison by train on March 18. Since Hinsdale County did not have funds for special guards, Packer was confined to a steel cell in the Gunnison County Jail. Although Packer had no money at this point, three lawyers agreed to represent him apparently because of the publicity that would get and the interesting aspects of this case. To make him more presentable, they promptly got their client a haircut and a new set of clothes.

Newspapers not only released Packer’s latest account of the death of his companions but accused him of all sorts of other crimes in Utah, Wyoming, and along the Continental Divide. He was described as “villainous,” “ugly,” and a “poisonous reptile.” Although no trial has been held, most newspaper articles already called for his death by hanging.

A grand jury presented five indictments against Packer. There was considerable legal wrangling on how to proceed because the crime may have taken place on Native American land, or at least in Colorado Territory, well before Colorado achieved statehood. Who had jurisdiction? The original indictment was amended, with changes in the wording about the place of the crime, and with a request for prosecution for only the Swan homicide rather than for killing all five members of the prospecting party. There was also a request to delay the trail because the residents of Hinsdale County had all been inflamed by the publicity. This last motion was denied.

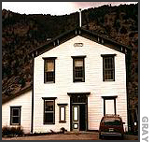

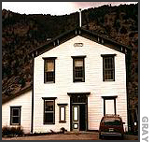

Hinsdale County Courthouse in Lake City, Colorado

Hinsdale County Courthouse in Lake City, Colorado

Alfred Packer’s trial began on April 6, 1883, at the Hinsdale County Courthouse in Lake City, Colorado, for the murder of the elderly Israel Swan. According to witnesses, Swan’s remains had shown evidence of a hand-to-hand struggle, implicating Packer in a much more violent episode than shooting a man in self-defense. Besides, it was not Swan he had claimed to shoot, but Bell. So why had Swan appeared to have struggled to save himself?

The second story of the courthouse was filled with curious observers while witnesses, attorneys, and lawmen filled the first floor. Prospective jurors were questioned under oath. Many were rejected because they knew they were going to be called as witnesses in the case or because they admitted that they had already formed an opinion of Packer’s guilt. Only five jurors were seated that morning. Late that afternoon, a jury of twelve was finally seated.

The trial began and witnesses were called. During the prosecution, testimony came out that Packer was in possession of Miller’s skinning knife and that he had plenty of spending money. There was testimony about the camp and the condition and identification of the bodies. The confession that Packer had first made and signed was introduced in evidence. One witness, Otto Mears, testified that he saw a Wells Fargo draft in Packer’s pocketbook and that Packer paid for good purchased from Mears using cash that he took from two billfolds.

Oddly, the coroner — the man in the best position to offer a professional analysis — did not testify at all. He wasn’t even called to do so. Since he had never recorded his observations of the condition of the remains, there was nothing in writing about the details to which the court could refer. In fact, no one who was experienced in criminal investigation testified at this trial. It was mostly a matter of who the jury would believe, and no one was a true eyewitness of the events save Packer himself.

When recalled later in the trial, Preston Nutter described a hole he had seen in a bone severed from one of the bodies, and in his layman’s opinion said it looked like a gunshot wound. He also described how the clothing of the deceased men had been “cut and ripped up.” He offered no explanation as to what he meant.

During the defense, Packer took the stand and testified for six hours on his own behalf, and in the process told several significant lies. He lied about his age, the nature of his military service, the fact that he had enlisted twice and been discharged twice, and the cause of his epilepsy, which he said had resulted from walking guard duty. He said he wanted to tell what had happened without interruption and then would agree to be questioned. He also asked that certain men who had testified against him be in court to be called upon since he had no other witnesses. Although this was somewhat unusual, the judge and attorneys agreed.

Packer then described how his party ran out of food, and how one by one, the men had given up goat skin moccasins, which they roasted and ate. Packer testified that he left camp in search of food and returned to find the others dead and Bell ready to attack him with a hatchet. Packer said he killed Bell in self-defense by shooting him “sideways through the belly.” (The prosecution later refuted this by stating that an examination showed Bell had been shot in the back. In 1989 Professor James Starr headed up a team that performed an exhumation at the burial site seeking forensic evidence. They reported in the Loveland Reporter-Herald in August 1989 that they found no evidence that any of the men had been shot.)

Packer testified that he didn’t know how long he remained in the camp after the killings. He admitted that the first story that he told when reaching the Indian Agency was not true and that he had lied again in the first confession that he made under interrogation.

After both sides had presented their case, the jury received its instructions and left at seven o’clock in the evening to deliberate. The next morning at nine o’clock, the jury was ready with its verdict. Packer was found guilty of the premeditated murder of Israel Swan. The members of the jury were polled, and they all confirmed the verdict. The judge then sentenced Packer to be hanged on May 19 in Hinsdale County.

Alfred Packer prison photo

Alfred Packer prison photo

Legend has it that Judge Gerry then pronounced the sentence as “Stand up yah voracious man-eatin’ sonofabitch and receive yir sitince. When yah came to Hinsdale County, there was siven dimmycrats. But you, yah et five of ’em, goddam yah. I sintince yah t’ be hanged by th’ neck ontil yer dead, dead, dead, as a warnin’ ag’in reducin’ th’ Dimmycratic populayshun of this county. Packer, you Republican cannibal, I would sintince ya ta hell but the statutes forbid it.”

What Gerry, a literate man, actually said, according to court documents, was, “Close your ears to the blandishments of hope. Listen not to the flattering promises of life, but prepare for the dread certainty of death.” He was apparently convinced that the motive for the murder was robbery, not survival or self-defense.

n a long statement, Gerry claimed that the sentence was painful for him to pronounce: “I would to God the cup might pass from me!” He mentioned that the murder was “revolting in all its details” and that the trial had been fair, with a jury of 12 impartial men. Gerry’s version was that the five victims laid down to go to sleep and Packer exploited their trust and vulnerability to effect his attack. Although he had been convicted only of the death of Israel Swan, the assumption in Gerry’s admonition was that Packer had willfully murdered the entire crew.

“To other sickening details of your crime I will not refer,” said Gerry. “Silence is kindness.” Clearly, he was referring to the cannibalism of human remains.

He did seem to think that Packer’s conscience had bothered him all these years and kept his crimes fresh in his mind. “You, Alfred Packer, sowed the wind. You must now reap the whirlwind… Your life must be taken as the penalty for your crime.”

Alfred Packer was condemned to be hanged on May 19, 1883, “until you are dead, dead, dead, and may God have mercy upon your soul.”

Contrary to many stories told years later, and even today (see Internet biographies), Packer was never charged with, tried for, or convicted of cannibalism, or crimes related to cannibalism.

But it was not over yet. The Maneater was not about to be hanged, and he had one more version of the story to tell.

Second Trial

The defense attorney immediately submitted thirteen reasons why Packer’s sentence should be reversed and why Packer should get a new trail. The Supreme Court agreed to consider the case, so the execution of Parker was stayed. Fearing a possible lynch mob, Packer was moved from Hinsdale County back to the secure Gunnison County jail.

It was not until December that Packer’s appeal finally came before the Supreme Court. The Court reversed the original sentence on the basis of changes in the homicide statute that had been made in 1881. The Court called for a new trial on the charge of manslaughter. Packer’s attorneys asked that the trial be moved from Lake City to Gunnison and this request was granted. Some later said that he had committed the crime on an Indian reservation, so by all rights he should have been tried in a Federal court, not a State court. At any rate, he was retried in 1886 for all five deaths — not just Israel Swan — on a different charge: voluntary manslaughter.

On August 2, the second trial began and again it was was difficult to impanel a jury. Evidence was presented as before, and Packer again chose to take a stand in his own defense. The jury came back with a finding of guilty of manslaughter.

The judge asked Packer if he had anything to say before sentence was passed. Packer made a rambling statement saying that he had only killed one man and that eventually the whole matter would be cleared up. The judge then sentenced Packer to forty years, eight years each for the killing of five men. So thirteen years after the event, Alferd Packer was finally convicted of his crimes.

On August 7, 1897, he wrote a letter to D.C. Hatch of the Denver Rocky Mountain News, with the longest version yet of the events that had taken place on that snowy mountain pass. Much of it was reprinted in the newspaper — though dramatized a bit.

He claimed that even before the six men set out, the entire party of 21 had been suffering from extreme hunger due to lack of planning and supplies on the trip from Utah. They were living on horse feed. Chief Ouray gave them assistance and they camped near his settlement. He told them that the mountains were impassible.

He then said that a man named Lutzenheiser and four others decided to go on across the mountains to the Agency. Ouray supposedly told them that it was only 40 miles away, when in fact it was 80. They soon ran out of supplies and cast lots to see who would become food for the others. But they spotted a coyote, and so spared anyone from being killed. Not long after, they came across a cow and killed that as well. The cow’s owner followed Lutzenheiser’s tracks and took him back to a camp. He found the others and aided them as well. When they revived, they started out again. (Packer claims that this was all a matter of court record.) They were again picked up near exhaustion and starvation.

At this point, Packer returns to the experience of his own party of six. They left about a week after Lutzenheiser’s party and took a different trail. Their provisions lasted about nine days. Three days after the food ran out, they cooked and ate their rawhide moccasins, wrapping their feet in blankets.

“Our suffering at this time was most intense,” he wrote, “such in fact, that the inexperienced cannot imagine.”

They kept going, since the snow quickly buried their trail from behind. He again points out that Wilson Bell suffered mental derangement from starvation, and everyone else was frightened of him. They finally descended to the lake fork of the Gunnison River and camped there. In the morning, Packer went to look for signs of civilization. When he returned, he saw Bell alone, just as he had related in a prior telling. But in this retelling, Bell came at him, he shot in self-defense, and then he realized that the other men were murdered.

“Can you imagine my situation? My companions dead and I left alone, surrounded by the midnight horrors of starvation as well as those of utter isolation?”

He could hardly believe he had ever returned in a rational frame of mind.

He sat down and saw the flesh that Bell had cut from Miller, cooking on the fire. But he did not partake. Instead, he laid it aside and covered his slain comrades. Finally in the morning, he ate some of the flesh and it made him feel ill. “My mind at this period failed me.” He did not want to believe it but he thought he must have eaten some of the flesh. He could not recall.

He stayed there for some time, he did not know how long, but in his wandering, looking for food, he somehow stumbled into the Agency. Without realizing it, he had traveled 40 miles.

Although by all reports, he came in looking quite healthy, he claims in this letter that he had to be taken care of for three weeks. He learned the Lutzenheiser and his party also made it out, and the rest of the 21 men who had begun the trip had come over with the Ute. Packer says that he confessed at once that he had killed Bell but had attributed the deaths of the others to Bell (not consistent with his initial confession before General Adams). He claimed that he had been unable to show anyone where his comrades had lain because deep snow had driven them back.

He was then arrested and he said that it was the sheriff who actually let him go and told him to go away. The sheriff apparently had taken compassion on him for all that he had been through. (He does not explain why, if he was freed by the law, he then had to live under an assumed name.)

“Am I the villainous wretch which some have asserted me to be?” he asks. “No man can be more heartily sorry for the acts of twenty-four years ago than I.”

He felt he had been unjustly dealt with, there having been no motive for why he would attack his fellow man. The ghosts of the dead men, he believed, knew that he was innocent.

The Maneater’s Last Days

In Canon City, Packer conducted himself as a model prisoner who had many visitors, tended a garden plot, and made handcrafts that he sold or gave away. Several times he filed a petition for pardon without success. In 1893 a Denver attorney took his case and argued that there was no precedent for having five indictments heard in one trial before one jury. The Colorado Attorney General answered that Pacer had consented to this and had not immediately entered an appeal and that now it was too late. Next, a commission was created to decide if due to his epilepsy or “insanity,” Packer should be released. It was the commission’s decision that Packer remain in jail.

While Packer’s 1899 appeal for pardon was still pending, Mrs. Leonel Ross O’Bryan, known as “Polly Pry,” entered the picture. She was associated with the Denver Post and was a colorful and powerful figure in American journalism for over three decades. Once she took an interest in the Alferd Packer case, she wrote many articles on his behalf. At that time, Charles S. Thomas was governor of Colorado, and he denied Packer’s latest request for a pardon in a statement published in the Denver Times.

On January 3, Polly Pry wrote a long article in the Denver Post attacking the governor’s decision to keep Packer in prison, stating that Packer was convicted “on the flimsiest sort of circumstantial evidence.” She also suggested that the governor was unduly influenced by Otto Mears, with whom the governor had discussed the case and the appeal.

Along with her article, Polly Pry printed the names of those who had signed a petition she had circulated on Packer’s behalf. It included the names of judges, key officials in Denver’s leading banks, the superintendent of Denver’s schools, the U.S. district attorney, numerous sheriffs, officials of the Union Pacific, Denver’s mayor, and Thomas M. Patterson, a rival politician who hoped to be appointed by the legislature to be the next senator from Colorado. It was well known that Governor Thomas had his eye on serving in that same senate position as soon as he completed his current term as governor. In addition, Packer had persuaded prominent men around the state, notably reporters and the owners of the Denver Post, to sign a petition on his behalf. The owners believed they could get Packer to be a side-show freak in the Sells-Floto Circus for their profit.

The sensational newspaper article was followed by more rebuttals and articles, for and against Packer. Then a bizarre turn of events occurred. A meeting was held in the offices of the Denver Post with editors Bonfils and Tammen and Polly Pry present. They met with William W. Anderson, a well-known Denver attorney. Earlier, Anderson had gone to visit Packer and secured a complete power of attorney. Believing this was not in Packer’s best interest, Polly Pry got Packer to revoke the power of attorney. An angry meeting meeting took place in the editor’s office. According to one account, Bonfils at one point leaped to his feet and struck the attorney beneath his eye. Bonfils and Tammen threw Anderson out of their office. Anderson jerked the door back open, pulled out his gun, and fired four shots, wounding both editors. Anderson was arrested and charged with assault.

When Anderson was tried for assaulting the editors, Packer was called in to testify about his earlier meeting and granting the power of attorney. Packer conducted himself well in court, and reporters began to write of him as a “misguided and persecuted man.” The jury could not come to an agreement in the Anderson case, and so he was found not guilty.

Then quite suddenly and without warning on January 7, 1901, outgoing Governor Charles S. Thomas, in his last act as governor of Colorado, granted Packer parole due to his “physical condition and advanced age.” He had served fifteen years of his sentence. Packer left the penitentiary and went straight to Denver to thank his old friend Duane Hatch and Polly Pry for working so hard to release him. During that first week of freedom in Denver, the state legislature chose the new U.S. senator from Colorado. Rather than choosing former governor Thomas, they selected Thomas M. Patterson, who had signed Packer’s release petition.

Packer saw the sights of Denver before moving to live in Sheridan, Colorado, where he tended a garden and kept rabbits and chickens. He spent much of his time in Deer Creek Canyon, about twenty miles from Sheridan. There he prospected among abandoned mining claims.

In 1906 Packer suffered an epileptic fit while in Deer Creek Canyon. He was found by a game warden who brought him to the home of Mrs. Van Alstine. He refused hospitalization and lingered on being tended in the home for several months. On April 17, 1907, Packer wrote to Colorado governor Henry A. Buchiel asking for an unconditional pardon. No action had been taken on this last request before Alferd Packer died on April 24, 1907.

He was buried at government expense, because he was considered a military veteran and for years had received a disability pension of $25 a month — for which he had filed from prison claiming his epilepsy had derived from his stint in the military.

According to the Littleton, Colorado newspaper, the Independent, Packer’s last words before he died were, “I’m not guilty of the charge.”

Years after the fact, in 1928 (or 1968), the citizens of Lake City erected a monument for the victims and threw a community fish fry. Exactly where the victims had been buried, however, proved to be a source of some contention.

In 1981, Governor Lamm denied Judge Kushner’s posthumous pardon of Alfred Packer. Then in 1989, an event occurred that drew the nation’s attention back to this man.

Another Look at the Victims

James E. Starrs, a law professor from The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. visited Gunnison one day in 1989 and heard some of the stories. Having long been curious about Packer’s two trials and his chosen defense, he looked for the spot where the victims had been buried. Townspeople directed him to various places like Dead Man’s Gulch, but no one was altogether certain. Starrs decided to ask the owners of the property on which a monument with the victims’ names had been erected if he could dig down and find evidence of the remains. They granted permission, he obtained insurance and several grants, and planned for an archaeological dig. He wrote about the experience in his own newsletter, Scientific Sleuthing Review.

Prof. James E. Starrs

Prof. James E. Starrs

The dig commenced on July 17, 1989, a bright sunny day, with a team that included anthropologists, archaeologists, photographers, student diggers, a lawyer, and other forensic personnel. Local media were on hand from around the state to document anything that was found. After checking the soil composition and pH level, Starrs started the dig with a team of experts who had brought in a ground-penetrating radar device. After they ran the machine over the area, they told him they suspected that whatever anomaly was below the surface was not very deep — possibly only a foot. They advised against using a backhoe, lest the shovel crush bones that might be close to the surface.

So the anthropologists and students took over with hand trowels and it wasn’t long before they discovered human remains. Digging for the rest of the day, they uncovered all five victims, laid out side-by-side. The bones were not intermingled, which made things easier for the forensic anthropologists, and they were photographed, boxed, labeled, and taken to the anthropology lab at the University of Arizona at Tucson.

There the bones were laid out and carefully examined, while a few pieces were sent on to the anthropological curator of the Smithsonian Institution, Douglas Ubelaker, for dating and age analysis.

Using known data, they managed to figure out the identities of each set of remains, and then did a more detailed examination for bone damage.

It can be difficult to make decisions about cause of death on skeletal remains unless there has been a wound from bullet, knife or blunt force that penetrated or broke a bone. In this case, given the various witness accounts, they did expect to find trauma, so they were careful to document everything.

One of the anthropologists, upon seeing the bones, had shouted that there was a bullet hole in one set of remains, but it turned out to be a hole that animals had gnawed and could not be ascertained as having been made by any weapon. (Nevertheless, the story got into the newspapers erroneously.) Three of the bodies had blunt force blows to the head, as well as cuts to the arms and hands, which Professor Starrs interpreted as defensive wounds. He also believed that nicks on the bones that appeared to have been made by a knife was evidence of defleshing.

While not everyone on the team agreed about how much actual support there was for making a definitive statement, Starrs went on record as saying that Packer was a murdering cannibal and liar.

The remains were reburied in a wooden box in the same spot, with a solemn ceremony.

Packer’s gun

Packer’s gun

In the meantime, in 1997, a curator for the collection of the Museum of Western Colorado in Gunnison, claimed to have discovered Packer’s revolver, an 1862 Colt. It had been collected from the massacre site, he said, when the victims were initially discovered. It was loaded, with three bullets in the chamber. According to some reports, including curator David Bailly’s, this discovery corroborates the details of Packer’s account — or at least of one of his confessions.

Starrs disputes that Packer owned such a gun and says there are no records that a revolver was recovered when the victims’ remains were found.

Regardless of whether Packer owned such a gun, the fact that he’d shot a bullet or two is no indication that he killed in self defense. He might have shot at some game, or he might have outright murdered one or more of his party. Even a bullet hole located on any member of the party would not clarify that issue.

Packer’s guilt or innocence may always remain a mystery, but his story continues to fascinate scholars and lay people alike.

The Legend Lives On

People have not forgotten Alfred (or Alferd) Packer. While a collected archive of documents exists in Colorado, from his prison record to the court cases to his bid for parole, other forms of entertainment poke fun at the man.

Video cover: The Legend of Alfred Packer

Video cover: The Legend of Alfred Packer

The University of Colorado at Boulder named their student cafeteria The Alfred Packer Memorial Grill, apparently as a derisive statement about the food served there.

A documentary movie was made, The Legend of Alfred Packer, as well as two musicals (which appear to be mostly a joke). One is supposedly called Cannibal! The Musical, and the other Alferd Packer — The Musical. The former is said to have been made by the creators ofSouth Park, while the latter is a clearly amateur attempt either at film-making or Internet practical jokes.

Roadside attractions on the way to Lake City, along “Cannibal Trail,” make light of the fact that five men died with caricatures and cannibal collectible dolls.

At the Hinsdale County Museum, one can see an alleged skull piece from one of the victims, the shackles that Packer wore in prison, and buttons from the clothing of the victims.

Thousands of tourists visit his grave every year.

Otto Mears was born in Kurland, Russia in 1840, the son of a Jewish Englishman and a Jewish Russian woman.

Otto Mears was born in Kurland, Russia in 1840, the son of a Jewish Englishman and a Jewish Russian woman.